1st International Seminar

At the roots of urban design.

National “schools” and prominent figures. An international perspective

15 May 2020

9.30am – 17.30pm

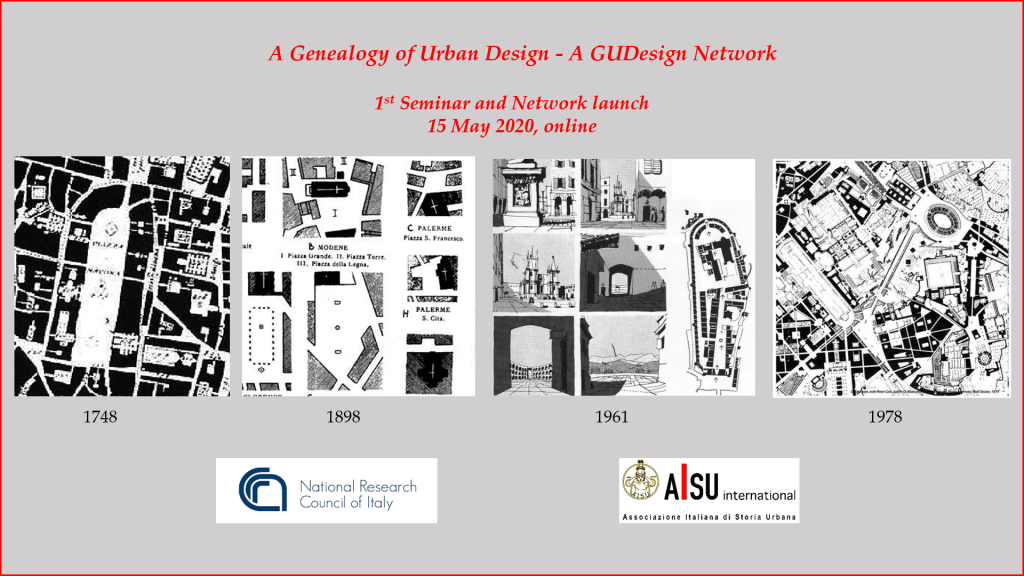

The purpose of this first seminar is to open the debate on the Genealogy of Urban Design, focusing on (i) the different terms/approaches used by various countries since the late 19th century, (ii) the institutionalization of this disciplinary area and its relationship with the birth of architecture and town planning schools, (iii) dissemination bodies, (iv) prominent figures involved. This Seminar, as well as the Network itself, are based on an interdisciplinary and comparative approach. In particular, this first Seminar aims principally to address major urban design histories (regarding schools of thought and interpretations), hopefully shaking our convictions, questioning long held beliefs, and posing questions, more than supplying answers. In a word, it aims to highlight whether or not there is truly a need for the GUDesign network!

Seminar Program

Abstracts

Art Public, Civic Art, Raumkunst and the Birth of Urban Design. Italian “Schools” and Prominent Figures Before and After the Second World War

Chairing: Giorgio Piccinato (Università di Roma Tre)

- Donatella Calabi (Università IUAV di Venezia), Early 20th Century Debate and the School of Architecture

1. In Italy, as elsewhere in Europe, at the beginning of the XX century, there is a phase in which the theorists insist, more than in the past, on the necessity to recur to the “artistic” principles in the urban transformation: a phase usually defined as the age of the birth of the “Stadt-baukunst” or of the “Civic art” (usually called "Arte di costruire la città", or "Arte Civica”, or “Arte urbana”, or “Estetica urbana” (expressions all literally translated from the German, or Austrian, or British, or Belgian terms). At the same time the notion of “patrimony” (heritage) heavily enters in the debate about Artistic City.

2. In the Twenties and Thirties town plans (mainly the so-called “Piani Particolareggiati”) often became “planivolumetrici” (three dimensional) where streets’ and squares’ design borrowed from studies by art historians (Albert Brinckmann, Platz und Monument of 1920) become a reference in designs by Marcello Piacentini or Giovanni Muzio. The town centre becomes a privileged object of investigation: sometimes having antiquity as a starting point, but in general focusing on the specific ‘character’ of each city. Quite often, architects-planners attempt to bring together past traditions with contemporary needs.

In parallel, however, professionals can assume also the role of the consultant. Some of them are called not only to design a city plan, but also to give ‘advice’ (as a medical doctor to the bedside of an ill man). In this sense, experts such as Joseph Stübben in Rome, or Gustavo Giovannoni in Verona, are asked to intervene on urban questions, with their knowledge and experience.

3. Many are the tendencies and hundreds the interesting figures to be studied. Speaking of the Italian Schools of Architecture, a period that need further investigation is probably the one after the second World War, when the relationships between “architecture” and “urbanism” (their distance, or their ‘unity’) became an important theme of debate .

Ludovico Quaroni, Giuseppe Samonà, Giancarlo De Carlo, Vittorio Gregotti (though quite different from each other), but all convinced of the strict existing linkages between the two ‘scales’ of the design activity, when confronted with the exponents of the Urbanism as an autonomous discipline (such as Cesare Chiodi, Virgilio Testa, Giovanni Astengo, Mario Coppa), probably offer us a tentative Genealogy of Urban Design.

- Rosa Tamborrino (Politecnico di Torino), L’Esthétique des Villes and the Development of Urban Conservation

This contribution focuses on the significance of an idea developed in a temporal framework as a turning point to define a new scenario for the discourse on cities, and its related glossary. The idea was that this discourse, with its practices, needed an esthetic perspective that included the past to design urban changes. Its assessment and validation would have been related to local characterization. The expression “esthétique des villes”, referring to the title of a book by the Belgian Charles Buls, is used in this context to identify this approach. The contribution mostly takes into account the temporal segment around the turn of the 20th century for discussing the theoretical framework of this concept, however, the impact of this approach should be surveyed till the reconstruction post WWI.

The contribution aims at enlightening the elements of the discourse and provide a chronology skeleton as well as identifying the francophone milieu where the book and its author represented one among other stakeholders sharing a similar idea. It will point out the relevance of collective associations, commissions and diffusion for surveying this period. It will remark the strong links between different actions. In particular, it will highlight some main aspects about the scale of thinking and visualizing a built environment and an urban image, the new attributes for cities, the search for a new link between the past and the future of a city.

The contribution finally aims at exploring how the idea of an “art public urbain” (urban public art) as a collaborative approach to a public space that capitalize on local identities through urban history’ diversity, represents both a key of interpretation for a reflection about cities and changes in a turning period and a legacy of European urban design which has to play a role in building a new knowledge.

- Guido Zucconi (Università IUAV di Venezia), The Notion of Urban Design in Milan’s Rationalism: Pagano, Marescotti, Bottoni

In the interwar period, Italian urban design seems to be particularly characterized by a strong link to national tradition –together with a significant stress on the notion of quality-. Even within the so-called Rationalist context, such a concern affects most of the suggested schemes. Simply said, modern architecture is called to match a highly qualified -as well as consolidated- custom in this specific area.

A striking exception emerges from the Milanese context, in particular from the group led by Giuseppe Pagano and his involvement in themes related to the “quartiere razionale”. Mostly based the notion of quantity, a series of large-scale projects will be expressed in different occasions such as the pages of “Casabella” and the Triennale Exposition. Special hints –to this direction- seem to directly spring from the Francfort CIAM of 1929 about “Existenzminimum” in which Griffini participated as the Italian representative , See, more in detail, urban schemes such as “Milano Verde”, “Città orizzontale”.

This new “Milanese” tradition will be continued after the second world war and the death of Pagano, especially throug the works of Diotallavi, Marescotti and Bottoni, as clearly shown in the lay-out of the QT8 new quarter in 1948.

- Elisabetta Pallottino (Università di Roma Tre), The Roman School and Urban Design

This paper questions the actual correlations of the definition "Scuola Romana" (Roman School); this is the name generically attributed to different architectural domains in the area of Rome, with its more or less structured manifestations of the early twentieth century (architecture, history of architecture, restoration, urban design as reported in the title).

In reading some insights into this school until today, it is possible to identify one of its most peculiar vocations: a unified vision of art and technique, past and present, history and architectural and urban design. Even though this vision was challenged during the second half of the twentieth century due to the historiography inspired by the modern Movement, today it can be indeed revamped and analyzed more in depth.

Il testo si interroga sulle effettive corrispondenze della definizione “Scuola Romana”, un nome che è stato genericamente attribuito ad ambiti diversi della cultura architettonica di area romana nelle sue manifestazioni più o meno strutturate del primo Novecento (architettura, storia dell’architettura, restauro, disegno urbano, per usare il termine del titolo).

La lettura di alcuni sguardi che le sono stati rivolti nel tempo fino a oggi, permette di individuare una delle sue vocazioni più peculiari: una visione unitaria di arte e tecnica, di passato e presente, di storia e progetto architettonico e urbano. Questa visione, che è stata messa in discussione nel corso del secondo Novecento per effetto della storiografia ispirata dal Movimento moderno, si presta oggi a essere nuovamente valutata e approfondita.

- Bertrando Bonfantini (Politecnico di Milano), Elements and Figures of Spatial Design in the Italian Post-War Reconstruction Plans

According to David Grahame Shane, in the introduction to his Urban Design Since 1945, “Patrick Abercrombie and John Henry Forshaw were the first modern authors to use the term ‘urban design’ in their County of London Plan for rebuilding the city after the wartime Blitz.”

In Italy, reconstruction plans for war-damaged settlements were established by decree at the beginning of March 1945. They are struck by the stigma of a widespread negative historical judgment. Nevertheless, or perhaps precisely because of this, the reconstruction plans represent, as Paolo Avarello pointed out, an “obscure age” of Italian urban planning to be quickly removed. They constitute an unknown season of the project for the urban, especially when you want to get out of monographic studies of individual cases or territories.

On the other hand, the reconstruction plans – as urban planning documents – are interesting precisely because of their intrinsic hybrid nature, between urban design and town planning: a bit detailed plans of immediate – modest and concrete – operation, a bit urban planning tools that reveal more ambitious intentions, for a wider reconfiguration and spatial reorganization of the settlement.

What are, then, the urban planning and design principles and criteria that one can recognize? Which spatial figures in the project do they highlight? Which intersections do they draw with lines of the post-war urban planning debate and research in Italy and in the international context?

This contribution attempts an exploration that feeds on what is perhaps the largest freely accessible collection of this documentation on Italian Reconstruction Plans, the online digital archive of Urban Planning Archives Network – RAPu.

European “Schools” and Urban Design Legacies since 19th Century and the Impact of Luìs Sert International Conference of 1956. An International Perspective

Chairing: Heleni Porfyriou (National Research Council of Italy – CNR)

- Ali Madanipour (Newcastle University - UK), Urban Design, Urbanization and Specialization

Some have suggested that urban design originated in a conference in 1956. In my presentation, I argue that urban design, broadly defined as the spatial organization and transformation of cities, is an ancient activity, the roots of which cannot be traced back to a precise time and place. In a brief analysis, I use two concepts of urbanization and specialization to examine the context of the 1956 conference. I try to show that the conference was not proposing a new activity, a new identity, or a new design philosophy, but it was an attempt to strengthen the role of design in a period of heightened development activity and within a fragmentary division of labour. As such, it was only one episode in the long history of urban design.

- Tom Avermaete (ETH Zurich - Switzerland), Crossing Boundaries: Transcultural Practice and Changing Urban Design Knowledge in the Post-War Period

This talk explores the crosscultural conditions in which urban designers work and the effect on the production of urban design knowledge. It focuses in particular on urban designers working in a condition of displacement – in other words in relation to cultures, far away or nearby, that are not their own.

The circulation of urban design approaches is not a new phenomenon. Along with the circulation of goods came the migration of urban ideas and construction practices. The apparent ease with which urban design approaches, urban models and drawings seemingly travel between cultures and continents makes it enticing to consider spatial practitioners as members of a global and cosmopolitan culture. However, transcending national boundaries and identities entails an encounter with the obstinate features of specific locales and particular cultural dynamics. The management of building activities, for instance, varies widely from country to country. National and local governments define specific legal frameworks that are appropriate to their social and economic geographies. Conceptions of publicness and privacy vary greatly within different cultural contexts.

How does this ‘clash of cosmopolitanism and localism’ affect the knowledge of urban design? What tools and methods can urban designers rely upon to perform within this condition? What kind of design strategies allow for mediation between endogenous and exogenous conditions? This talk will examine the abovementioned issues by first focusing on a crucial moment: the post Second World War wave of transcultural expertise that emerged in the ‘global South’ after decolonization, often under the header of ‘development aid’. It aims to unravel mechanisms of urban knowledge production specific to the postcolonial context and the processes of decolonisation, characterised by shifting political and economic conditions as a result of the Cold War.

Today we can look at the experiments of that period from a critical distance, and ponder on the roles, instruments and knowledge that key urban planners of that time employed – and what they have resulted in. The talk will refer to relevant figures for the construction of transcultural practice, comprising Constantinos Doxiadis, Michel Écochard, Jacqueline Tyrhwitt, Otto Koenigsberger, Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, as well as the Collective of Nordic architects.

- Kalliopi Amygdalou (National Technical University of Athens - Greece), In Search for Urban Reform: Ernest Hébrard and Henri Prost in the Near East

In the early twentieth century a group of French Beaux-Arts graduates ‘took over’ the Villa Medici and pushed for a turn from the study of ancient columns to the study of the urban scale. Tony Garnier, Henri Prost, Ernest Hébrard and other recipients of the prestigious Prix-de-Rome carried out a soft revolution against the academy by looking at ancient sites for answers to contemporary urban problems. This group was also involved in the reformist Musée Social (1895) and the Societé Française des Urbanistes (1913). Soon, they started implementing their ideas in colonial and non-colonial foreign contexts – such as Greece and Turkey- with the ultimate dream of also implementing them at home. This presentation focuses on the emergence of urbanism in France and addresses the turn of the 20th century neither as a mere preparatory period for what was to follow, nor as a period in which urban planning had been fully established across architectural institutions. Rather, it looks at the role of a group of architects who shared a strong vision, developed new tools and tried them out abroad and at home, triggering a mobility of knowledge between metropolis and ‘periphery’ while establishing French urbanism along the way.

- Fabio Mangone (Università di Napoli “Federico II”), Historicism and Urban Design: the Case of Naples, Italy, 1861-1926

The paper argues that the culture of the historicism of the nineteenth century, still vivid even in the first decades of the Twentieth century, was part of the cultural heritage shared not only among the architects educated at Academies of fine arts but also among the engineers formed at the Polytechnic schools. Moreover, the essay demonstrates how the historicist ideas permeated the projects both on the architectural and the urban scale.

The city of Naples, in the years between the Italian Unification and the advent of Fascism, is a particularly significant case study to demonstrate the aforementioned theses, for the richness and variety of the project proposals that – before and after the long season of the city renewal renowned as “Risanamento” – had to face the cogent problems related to urban hygiene, social housing, and city circulation, from the most comprehensive perspective of the urban design.

Relevant figures of architects and engineers – albeit distinctively different, such as Errico Alvino and Gustavo Giovannoni, or Lamont Young and Giovan Battista Comencini – renovated circumscribed city areas with particular attention to the urban conformation, starting their design from the historic models, with a constant interest for English, French, as well as Italian experiences and examples.

- Ines Tolic (Università di Bologna), The urban front. Designing cities and settlements in the developing world

It has been argued that the urban design concept originated at Harvard University, as Josep Lluís Sert, Sigfried Giedion, and Jaqueline Tyrwhitt attempted to respond to the challenges of younger CIAM members. However, it should not be considered a coincidence that, while the first Urban Design Conference was being prepared, the Congress of the United States was making available funds aimed at improving American cities. In fact, it is quite likely that the need for a generalized debate on the fate of the contemporary city resulted precisely because of these economical resources, rather than because of an attempt to start an intergenerational dialogue within the CIAM group.

In order to establish Urban Design as a professional field, a two-days long “invitation conference” was organized at Fogg Museum on April 9 and 10, 1956, and sponsored by the Faculty and Alumni Association of the Graduate School of Design. Invitation letters, sent out only in February, stated that the main goal of the event was “to try to find a common basis for the joint work of the Architect, the Landscape Architect and the City Planner”. As such, Urban Design was to be considered a multidisciplinary profession, whose main goal was to solve “the frequent absence of beauty and delight in the contemporary city”. Having as focus civic values and an overall aesthetic quality of the urban environment, urban design was supposed to contain the greed of real estate developers and their desire for “quick return of investment”. Finally, urban design was pointing towards a better future with the goal to contribute in “shaping (or reshaping) of the American urban scene”.

Urban design, as it was presented in 1956, was at the same time a vague and a sophisticated concept. Tailored on the needs of a first world country and its values, it implied the availability of conspicuous economical resources, it presumed the existence of well-trained professionals and it took for granted a certain cultural level of the final beneficiaries. Such conditions lacked in the majority of countries around the world, the population of which had basic housing problems. For these, Harvard’s urban design was to stay confined in a utopian realm.

During 1950s however, intergovernmental organizations and international financial institutions started to show some interest in these rapidly decolonizing Third world countries. Attempts to improve the housing standard of local populations increased exponentially after president Dwight D. Eisenhower presented to the Congress of the United States his “doctrine”. In fact, since January 1957, conspicuous founds were made available and used to implement housing programs - and American political control - in countries under the Soviet threat. It is not a coincidence that, following Eisenhower’s speech, planners like Constantinos A. Doxiadis, international organizations like the United Nations and even the Harvard University itself increased enormously their presence in the Global South. According to Anthony King and Nancy H. Kwak among others, in this period typically Western concepts of democracy and capitalism were translated into projects and plans for the so-called Developing countries. Avoiding to deal with the political goals of these actions or with their often controversial achievements, my presentation will attempt to investigate the Third world declination of the urban design concept and its yet underestimated role for the emergence of a global urban agenda.